02-12-2025

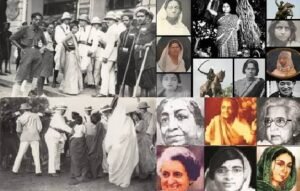

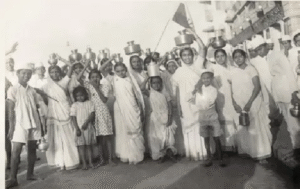

NEW DELHI: In India, a set of recently discovered photographs is drawing attention to the role of women in one of the country’s biggest anti-colonial movements, known as the civil disobedience movement, led by Mahatma Gandhi in 1930-31.

The images do not simply capture female participation. They are visual proof of how women commanded and dominated political activity, often relegating men to the sidelines.

The images do not simply capture female participation. They are visual proof of how women commanded and dominated political activity, often relegating men to the sidelines.

In April 1930, Gandhi concluded his pivotal salt march, breaking the British monopoly on salt production, a charged symbol of colonial misrule. Raising a handful of muddy salt from the sea, he declared himself to be “shaking the foundations of the British Empire”.

Afterwards, Gandhi presided over waves of civil disobedience protests, encouraging supporters of the Indian National Congress to manufacture contraband salt, boycott foreign goods, and face down phalanxes of lathi-wielding policemen. Just a few months before, the Congress had declared purna swaraj (complete independence) as its political objective for India.

Historians have long recognized the civil disobedience movement as an important turning point in Indian politics.

First, women joined anti-colonial activities in greater numbers. When Gandhi began his salt march he forbade women from joining, but several female leaders eventually convinced him to accord them a greater role.

Second, Congress leaders harnessed modern media technologies like radio, film, and photography, which helped their political struggle reach an international audience.

About 20 years ago, one album of photographs from the movement appeared at a London auction. Tipped off by an antiquarian dealer in Mumbai (formerly Bombay), the Alkazi Foundation, a Delhi-based art collection, acquired the album.

Small in size with a coal-gray cover, the album gave few clues about its provenance.

Scrawled on its spine were the words “Collections of Photographs of Old Congress Party, K. L. Nursey.”

No one knew the identity of KL Nursey. Typewritten photo captions were brief and rife with spelling and factual errors. The album remained undisturbed in the Alkazi Foundation’s collections until its curator and two historians from Duke University began to reexamine it in 2019.

No one knew the identity of KL Nursey. Typewritten photo captions were brief and rife with spelling and factual errors. The album remained undisturbed in the Alkazi Foundation’s collections until its curator and two historians from Duke University began to reexamine it in 2019.

They were shocked by what they found.

Despite their unknown origins, the photographs of the Nursey album told a dramatic and detailed story.

Pictured here were the streets of Bombay, tense and bristling with thousands of volunteers aligned with the Congress. Unlike earlier photographs of political activity in India, these are not posed-for images; they capture violent confrontations with police, wounded volunteers loaded onto ambulances, boisterous marches amidst monsoonal downpours, and endless streams of protesting men and women through Bombay’s Indo-Gothic streetscape. There is an electric energy running through the black-and-white images.

Above all, the album brings to light, perhaps better than any other source, how women used the civil disobedience movement for their empowerment.

“We were immediately struck by the emphasis on women in action,” says Sumathi Ramaswamy of Duke University, who, along with her colleague Avrati Bhatnagar led the detailed examination of the album.

As recently as the noncooperation movement in 1920-22, women played a far more circumscribed role. Now, however, women’s involvement took a quantum leap.

Pressmediaofindia

Pressmediaofindia