04-09-2021

By SJA Jafri + Bureau Report

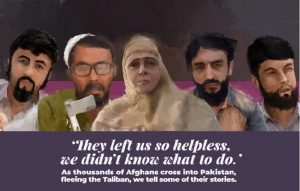

KARACHI/ KABUL: As the world watched the frantic evacuations from Kabul’s airport, thousands of people were making their way to Afghanistan’s border with Pakistan on foot and in any vehicles they could find, far from the glare of news cameras.

KARACHI/ KABUL: As the world watched the frantic evacuations from Kabul’s airport, thousands of people were making their way to Afghanistan’s border with Pakistan on foot and in any vehicles they could find, far from the glare of news cameras.

Officially, the border is closed to all except those with valid paperwork for medical reasons, work or to see family on either side.

Yet, thousands of Afghans have streamed through the Spin Boldak border crossing in Afghanistan’s southeastern Kandahar province into the Pakistani town of Chaman.

Refugees twice

Local sources say that, for weeks, up to 5,000 Afghans had been crossing daily until August 15,  the day the Taliban took control of Kabul; that number has since doubled.

the day the Taliban took control of Kabul; that number has since doubled.

Today, Pakistan is home to more than 1.4 million registered Afghan refugees, many of whom entered the country some 40 years ago, after the Soviet invasion in 1979.

Hundreds of thousands more joined them after the US invasion in 2001.

By 2002, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) counted three million Afghan refugees in Pakistan. Many returned to Afghanistan and the numbers dropped until the US troop withdrawal began this year.

Pakistan’s government insists it is unprepared for a refugee influx and is considering options for how best to manage the new arrivals.

After negotiating the crossing, most refugees make their way to Pakistan’s main urban centres, seeking shelter, safety and, in some instances, the means for an onward journey.

In a bustling corner of Karachi, a sprawling metropolis of more than 20 million people in southern Pakistan, a sizable Afghan community has lived for decades.

Many of them came as refugees in the 1980s.

Many of them came as refugees in the 1980s.

Behind the narrow, broken streets near the city’s largest bus terminal, the neighborhood is covered with low-rise apartment complexes, the roads choked with motorcycles and bicycles.

In the corner of one such apartment compound, there are several homes with their doors wide open.

A group of men sits on the stoop as young boys play in the concrete yard.

Some of them have just made their way from Afghanistan. They had to brave violence and risk being turned away or arrested at security checkpoints as they fled a country in the throes of transition.

It is a journey some have endured before.

This is the second time they become refugees. Some, who have refugee ID cards issued by the Pakistani government, know they will have certain rights and protections guaranteed in their host country but others have entered without any paperwork at all. Here are some of their stories.

Mohammed Azeem is an ethnic Tajik who worked in a bakery while pursuing an engineering degree in Kabul.

Azeem fled Kabul province after two of his friends were brutally killed by the Taliban just over two weeks ago.

He and his friends had given Afghan forces information on Taliban hideouts in the area in 2016, “for 1,395 Afghani ($20)”. They were together when the Taliban fighters rounded them up.

He and his friends had given Afghan forces information on Taliban hideouts in the area in 2016, “for 1,395 Afghani ($20)”. They were together when the Taliban fighters rounded them up.

The fighters took photographs of the young men before torturing them.

“They cut off his nose and his ear, fingers, and toes, in front of my eyes. I managed to run away from there,” explains Azeem.

The panic on his face creeps into his voice as he recalls that day. He looks around to see who can hear him. His voice breaks, but he continues.

He fled Kabul on August 17, within 48 hours of the Taliban encircling the Afghan capital.

Azeem’s father had to borrow money from a neighbor to pay for his son’s journey to safety, which took two days and three nights of non-stop travel.

At Spin Boldak, Pakistani border control guards initially refused him entry because he had neither the ID card nor refugee paperwork.

“I showed them this,” he says, pointing to a medical scan rolled up in his backpack, “[I] said I’m here for my life, please helping me. My life is in danger, the Taliban are following me.”

He was fortunate enough to be allowed to enter but now finds himself destitute, in a strange country where he does not speak the language and cannot see a way forward.

“I had been sleeping outside the mosque near the bus station because I don’t know where to go and who to ask for help,” he told Al Jazeera of his first few days in Karachi.

“I had been sleeping outside the mosque near the bus station because I don’t know where to go and who to ask for help,” he told Al Jazeera of his first few days in Karachi.

“One of the rickshaw drivers told me about this compound and said more refugees are here, but I don’t know who to speak to.”

“I am worried about my future, what will be my destiny?” he asks, “because I wanted to be an engineer. I want to learn and I want to do something.”

Shamayl is a nurse’s aide, a job she has done for nearly 20 years.

She fled Afghanistan’s Baghlan province a month ago as Taliban fighters came to her town before taking the province on August 10.

They made it difficult for her to work, she says, or even be safe in her own home.

Shamayl travelled with her husband and daughter for four days, initially by bus then on foot, to reach Karachi.

The tall 44-year-old mother of two is gaunt, her features drawn and eyes red-rimmed from the stress of the last few weeks “when the Taliban came into our town, the entire atmosphere changed,” she says, “because of them, there were bombs from the sky. Many were wounded.

“The Taliban made life so difficult…we had no choice but to come to Pakistan.

“I sent my 16-year-old son out to work because we were in debt.”

The Taliban took her eldest son while he was out for work – he is still missing.

“(The Taliban) break into homes… come in and take food, beat people in the house, and threaten us because we have a young daughter. She is 14. I am very scared for her,” says Shamayl.

“(The Taliban) break into homes… come in and take food, beat people in the house, and threaten us because we have a young daughter. She is 14. I am very scared for her,” says Shamayl.

“I had to protect her. My wish is to go to Canada or Turkey. My daughter is studying; I want her to continue studying. I want her to better her life.”

Her husband, who worked in a roadside kebab diner, was badly beaten by the Taliban. They broke both his knees.

“They don’t care if a man or woman is old or young, no respect, they will terrorize and physically assault [us]… If they see a young girl in the house they have ransacked, they will threaten to take the girl,” she says.

In Shamayl’s case, the Taliban threatened both her son and daughter.

“My son, they wanted to take for jihad [as a forced conscript] and the daughter to marry,” she explains.

“We realized we couldn’t live there any longer. We left quietly in the middle of the night.”

Since taking over Kabul, the Taliban’s official spokesman has dismissed the claim that the group is forcing women to marry its fighters as “baseless propaganda”.

Shamayl’s family decided to make their way to Karachi; they knew nobody there and had no documents to cross the border but they managed to enter the country that will now be their temporary home.

“I’ve been here for a month. And everything is expensive here. I’m not sure how we will survive,” she says.

“There is corona (virus), there are so many issues. I just want to go abroad. I went to the post office to send my application for Canada, America, and Turkey,” she says.

“There is corona (virus), there are so many issues. I just want to go abroad. I went to the post office to send my application for Canada, America, and Turkey,” she says.

“I still haven’t heard back.”

Ahad, 50, sits leaning on an aluminum crutch he props in front of him, pushing his round glasses up as they slide down his nose.

He had lived in Karachi for nearly 20 years before returning to his country to serve in the Afghan armed forces after the US invasion in 2001.

As a proud Afghan citizen – no longer a refugee – he joined the Afghan National Army when US forces first started training them in December 2002.

Ahad says he wanted to serve his country, a place he felt he belonged to despite having barely lived there.

During his time as an Afghan soldier, he was posted to Kandahar, Zabul, Terenkot, Jalalabad, and others; he feels lucky to have had the opportunity to see different parts of his country.

Ten years passed in relative “peace” for Ahad, before the fight against the Taliban escalated.

“It’s not as if the army didn’t fight back, why we should give in to brutality?” he says.

“In the end, finally, they gave in to brutality,” he says with sadness in his eyes.

The fact that his life’s work ended within days is a huge loss for Ahad but he is no stranger to loss.

The Taliban killed one of his brothers, who was also in the army, in the recent fighting “and another brother was killed five or six years ago and so was my father in a crossfire (between the Taliban and the Afghan national army),” he says.

The Taliban killed one of his brothers, who was also in the army, in the recent fighting “and another brother was killed five or six years ago and so was my father in a crossfire (between the Taliban and the Afghan national army),” he says.

He left Baghlan province about four months ago with his mother, wife, and children to get away from the mental torture and physical harassment that they had to endure at the hands of the Taliban fighters.

“In the night, when we would fall asleep, they would knock throughout the night – and demand we give them space in the house to sleep,” he says.

“The Taliban vandalized my door, the house walls, the glass windows, just because I was in the army. They left us so helpless; we didn’t know what to do.”

During the day, the fighters would summon him and insist he was working against Islam because he was working with foreigners. They would push him around.

He tried to reason with them, explaining to them that although foreigners had been paying his salary, he worked for his country.

“It wasn’t un-Islamic to work in the armed forces – I say La ilah ila Allah (the Muslim Shahada), you also say La ilah ila Allah – what is the difference?”

His reasoning did not convince them. So he knew he had no choice but to leave.

“I’m wearing this shirt, and I took one more set of clothing, locked up my house, and left for Karachi,” he says.

He chose not to carry his Afghan army identification card with him to avoid being identified as a former soldier at Taliban checkpoints.

Border control in Pakistan let him through because of his medical needs.

Border control in Pakistan let him through because of his medical needs.

During his time as a soldier, he had sustained an injury to his leg, leaving him unable to walk without a crutch.

He says he is fortunate to have navigated the risks.

“I lived in Karachi before, I am back here. I don’t want to go back. There is nothing to go back to.”

Two brothers from Kunduz city with their young families, each with a newborn baby, crossed the border from Afghanistan into Pakistan two weeks ago.

They had to leave their parents behind because they did not have enough money to pay for their journey.

One of the men is 19-year-old Asadullah, a man of slight build and heavy eyes.

He hopes they can save enough money in Karachi to send for their parents.

Asadullah’s wife’s family lives in Karachi, but he had never been to Pakistan before and speaks very little Urdu.

In Kunduz, he had started driving a rickshaw to try to get out of a cycle of unemployment and hunger.

So he was surprised when he found himself picked up by the Taliban and questioned brutally.

“They first hit me for days and wanted me to tell them what work I really did. I was just a rickshaw driver,” Asadullah says.

Normally, he says, “the Taliban didn’t bother those people who work in the bazaar, or hotels or small shops.

“Anyone who works in the army, the police, in the government, they won’t spare you.”

“The Taliban don’t care what you try to explain, they will pick you up if they want, and that’s it.

“At first, they will beat you up, and when you submit to them, they will force you to work with them,” he says as he looks down as if trying to find the words to express what he went through.

“At first, they will beat you up, and when you submit to them, they will force you to work with them,” he says as he looks down as if trying to find the words to express what he went through.

As the Taliban began setting up roadblocks on the roads out of Kunduz, the two families got on a night bus that brought them first to Kandahar and then to Spin Boldak.

They spent the four-day journey fearing the worst, that their bus would be stopped by the Taliban but it was not stopped, and they crossed.

The border officials allowed them entry because his wife’s family lives in Karachi.

They look forward to making it their new home.

“There is no war here, there is no fighting, it is good here,” he says.

Samiullah is Asadullah’s elder brother.

As a butcher in Kunduz, he made a decent living, but the day-to-day fighting between the Taliban and the armed forces got too much for him.

“You can’t study, you can’t do business. Every day the fighting, the bombs, and air bombardment was getting worse and worse,” he recalls.

“The government forces and Taliban made it impossible for people like us. We had no choice but to leave. Innocent people were getting killed.”

Samiullah blames former President Ashraf Ghani’s overthrown government for the Taliban takeover.

“We were not happy under the Ashraf Ghani government. Ever since he took power, there has been more fighting, more war,” he says.

Samiullah came to Pakistan in search of peace and safety; he knows they were lucky to make it across without documents, so he wants to make it work for himself and his family.

He believes they can have a better life in Karachi and wants to work to save enough for his parents to join them.

“I don’t have a job yet, I need to find work. I am a butcher, I want to do that again,” he hopes.

In spite of his skills, his position is tenuous.

Pakistan said it is not currently registering any new refugees and, without paperwork, it will be difficult for him to find a job, and he knows that.

“We can’t do anything without ID cards. I only have paperwork from Afghanistan.”

(Names have been changed to protect their identity)

Pressmediaofindia

Pressmediaofindia