22-07-2020

By SJA Jafri

STOCKHOLM/ RIYADH/ TEHRAN/ WASHINGTON/ JERUSALEM: When countries start dabbling in nuclear energy, eyebrows raise. It’s understandable, topping the spread of nuclear weapons while allowing countries to pursue civilian nuclear programs has proven a tough and sometimes unsuccessful balancing act for the global community.

So when atom-splitting initiatives surface in a region with a history of nuclear secrecy and where whacking missiles into one’s enemies is relatively common, it is not just eyebrows that are hoisted, but red flags.

So when atom-splitting initiatives surface in a region with a history of nuclear secrecy and where whacking missiles into one’s enemies is relatively common, it is not just eyebrows that are hoisted, but red flags.

Right now, warning banners are waving above the Arabian Peninsula, where the United Arab Emirates (UAE) has loaded fuel rods into the first of four reactors at Barakah – the Arab world’s first nuclear power plant.

Roughly 388 miles west, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) is constructing its first research reactor at the King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology.

The UAE has agreed not to enrich uranium or reprocess spent fuel. It has also signed up to enhanced non-proliferation protocols and even secured a coveted 123 Agreement with the United States that allows for the bilateral sharing of civilian nuclear components, materials and know-how but that has not placated some nuclear energy veterans who question why the Emirates has pushed ahead with nuclear fission to generate electricity when there are far safer, far cheaper renewable options more befitting its sunny climate.

Like the UAE, Saudi Arabia insists its nuclear ambitions extend no further than civilian energy projects. But unlike its neighbor and regional ally, Riyadh has not officially sworn off developing nuclear weapons.

The kingdom’s de facto leader, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS), has publicly declared his intention to pursue nuclear weapons if Iran gets them first.

The specter of the Saudi-Iran Cold War escalating into a nuclear arms race is not beyond the realm of possibility. There are growing concerns over the nuclearisation of the Arabian Peninsula and where it could lead the Gulf and the Middle East – a volatile region that experts warn could be opening itself up to superpower proxy fights on a nuclear scale.

The specter of the Saudi-Iran Cold War escalating into a nuclear arms race is not beyond the realm of possibility. There are growing concerns over the nuclearisation of the Arabian Peninsula and where it could lead the Gulf and the Middle East – a volatile region that experts warn could be opening itself up to superpower proxy fights on a nuclear scale.

Saudi Arabia’s nuclear ambitions date back to at least 2006, when the kingdom started exploring nuclear power options as part of a joint programme with other members of the Gulf Cooperation Council.

More recently, the kingdom laced its nuclear plans into MBS’s “Vision 2030” blueprint to diversify the country’s economy away from oil.

Nuclear energy, the kingdom argues, would allow it to export crude it currently consumes for domestic energy needs, generating more income for state coffers while developing a new high-tech industry to create jobs for its youthful workforce but if a bountiful economic harvest is the goal, nuclear energy is a poor industry to seed compared to renewables like solar and wind.

“Every state has the right to determine its energy mix. The problem is this: nuclear costs are enormous,” Paul Dorfman, Honorary Senior Research Fellow at the Energy Institute, University College London and founder and chair of the Nuclear Consulting Group, told sources. “Renewables may be between one-fifth and one-seventh the cost of nuclear.”

Utility-scale, average unsubsidized lifetime costs for solar photovoltaic were around $40 per megawatt hour (MWh) in 2019, compared to $155 per MWh for nuclear energy, according to an analysis by financial advisory and asset manager Lazard.

“There are no economic or energy policy or industrial reasons to build a nuclear power plant,” Mycle Schneider, convening lead author and the publisher of the World Nuclear Industry Status Report, told Al Jazeera. “If countries decide to build a nuclear power plant anyway, then we have to discuss other issues that are actually the drivers for those projects.”

“There are no economic or energy policy or industrial reasons to build a nuclear power plant,” Mycle Schneider, convening lead author and the publisher of the World Nuclear Industry Status Report, told Al Jazeera. “If countries decide to build a nuclear power plant anyway, then we have to discuss other issues that are actually the drivers for those projects.”

Saudi Arabia’s King Abdullah City for Atomic and Renewable Energy did not respond to Al Jazeera’s request for an interview.

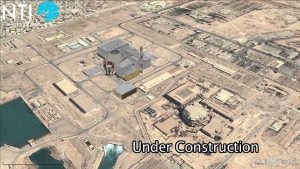

The Saudis have invited companies to bid on building two power reactors, but to date have not awarded a contract. While those plans remain on the drawing board, the kingdom is pressing ahead with construction on its first research reactor.

And there are troubling signs surrounding the project.

The Saudis announced in early 2018 that they had broken ground on a small research reactor that would be operational by the end of 2019.

Like most nuclear projects, Riyadh’s has fallen behind schedule. But there is strong evidence that the Saudis are pressing ahead with renewed vigor.

Bloomberg news reported that satellite photos taken in March and May of this year revealed that the Saudis have built a roof over the reactor – a development that is alarming nuclear experts because the Saudis have not yet invited the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to monitor the site and inspect the reactor’s design.

“What it does tend to infer is problematic,” said Dorfman. “Key to IAEA surveillance and regulations is signing up to non-proliferation treaties. In other words, questions of enrichment and how you deal with substances that flow out of nuclear reactors in terms of future weaponisation.”

“What it does tend to infer is problematic,” said Dorfman. “Key to IAEA surveillance and regulations is signing up to non-proliferation treaties. In other words, questions of enrichment and how you deal with substances that flow out of nuclear reactors in terms of future weaponisation.”

Saudi has signed the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), which obligates it to have a Comprehensive Safeguards Agreement with the IAEA. But those agreements do not allow IAEA inspectors to come sniffing around whenever they like on short notice.

That level of access is only granted when a country signs an Additional Protocol with the IAEA – something the UAE has done, but which the Saudis have not.

Nor is Riyadh obligated to make this move, because the Saudis are currently operating under a Small Quantities Protocol (SQP) that exempts states with nuclear ambitions from IAEA inspections.

The presumption is that the countries operating under the SQP do not have enough nuclear material to warrant that level of intrusiveness. But experts say the Saudis will not be able to hide behind the small quantities’ fig leaf once they switch on the reactor.

“It will have more than a small quantity of material, maybe not a large one, but more than the limit under this (SQP) agreement,” Henry Sokolski, executive director of the Nonproliferation Policy Education Center, told sources. “Instead of owning up that they need to change the agreement and reaching an understanding with the people in Vienna (where the IAEA is based), they’re playing this out to the last second that’s not a great look.”

Procrastination is not without its downsides. Riyadh does not have a 123 Agreement with the US that allows for bilateral civilian nuclear cooperation, despite efforts to negotiate one.

Procrastination is not without its downsides. Riyadh does not have a 123 Agreement with the US that allows for bilateral civilian nuclear cooperation, despite efforts to negotiate one.

A 123 Agreement would give Riyadh a seal of approval from Washington, while it would open the door for US companies to throw their hats into the ring to reap profits from building reactors for the kingdom.

While US lawmakers in Congress have not been willing to turn a blind eye to Saudi Arabia’s bad behavior, the administration of US President Donald Trump has not let it get in the way of fostering closer ties with the kingdom.

Trump, for example, has vigorously supported conventional weapons sales to the Saudis despite Riyadh’s abysmal record on human rights, while his son-in-law Jared Kushner has forged a close relationship with MBS.

This disconnect between Congress and the White House on Saudi policy was noted in a recent report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) – a non-partisan Congressional watchdog – that found that the Trump administration may not have been as transparent as it should be with Congress over nuclear negotiations with the Saudis.

According to the GAO, the sticking points holding up a 123 Agreement between the US and Saudi include Riyadh’s failure to agree to refrain from enriching uranium or reprocessing plutonium – key ingredients in nuclear weapons – or to sign an Additional Protocol with the IAEA.

“They don’t want to sign up to that. And you’ve got to ask the question: ‘Well, why? what’s the problem?'” said Sokolski.

“We know that looking at other military acquisitions, particularly in the missile arena, that the Saudis have a bad habit of doing things in secret if they think it’s controversial,” Sokolski added. “Would nuclear be treated the same way as missile acquisitions? If so, this is another lack of transparency you’ve got to be concerned about.”

“We know that looking at other military acquisitions, particularly in the missile arena, that the Saudis have a bad habit of doing things in secret if they think it’s controversial,” Sokolski added. “Would nuclear be treated the same way as missile acquisitions? If so, this is another lack of transparency you’ve got to be concerned about.”

Saudi Arabia is not the only Middle East nation playing its nuclear cards close to the vest. The region has a well-established history of it.

Iraq had a covert nuclear weapons programme that was dismantled following the US invasion during the 1991 Gulf War.

Libya came clean about its clandestine nuclear weapons program in 2003.

In the early 1990s, Algeria signed the NPT and agreed to IAEA inspections after it came to light that it had built a nuclear research reactor with Chinese help.

A suspected reactor under construction in Syria was destroyed by the Israeli military in 2007, though Damascus insisted the facility was non-nuclear.

Iran built nuclear facilities that were not declared until 2002. In 2005, after the IAEA determined that the country had breached its obligations under non-proliferation protocols, the US, United Nations and European Union economically pressured Tehran to the negotiating table, resulting in the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action with world powers to curb Iran’s nuclear ambitions.

That deal is now slowly unraveling under the Trump administration, which unilaterally withdrew from it in 2018 and launched a “maximum pressure” campaign of relentless economic sanctions in an attempt to bend Iran to Washington’s will.

“Iran is serious and it is a huge concern,” said Dorfman. “It is also a huge concern that America has withdrawn from active engagement.”

Though Washington has taken hard lines against Iraq’s and Iran’s nuclear programs over the years, it has benignly neglected what is arguably the granddaddy of nuclear cat and mouse in the Middle East – Israel.

Israel has not signed the NPT, nor does it allow IAEA inspections. And for decades, it has neither confirmed nor denied it has a nuclear weapons program, even though it is widely believed to have an arsenal that the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute numbers at 90 warheads.

Israel has not signed the NPT, nor does it allow IAEA inspections. And for decades, it has neither confirmed nor denied it has a nuclear weapons program, even though it is widely believed to have an arsenal that the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute numbers at 90 warheads.

Israel’s long-standing policy of nuclear opacity – and Washington’s acceptance of it – sets a poor precedent, say experts, for nuclear transparency from other Middle Eastern nations.

“It’s unhelpful,” said Sokolski. “It may well be that it’s in their [Israel’s] interest not to admit that they have them (nuclear weapons), but I think other countries, including the United States, their credibility talking about this is at risk when we aren’t willing to say, officially, ‘yeah, of course, they have nuclear weapons’.”

Sokolski believes Israel may even have come to regret going nuclear.

“Suppose the Israelis with 20-20 hindsight, some of them ought to be scratching their head on just how useful their own nuclear weapons have been,” said Sokolski. “There’s an argument that they actually would now, at a minimum, and maybe before, been better off not bothering.”

MBS has been candid about what would drive the kingdom to pursue nuclear weapons, telling US news outlet CBS in 2018 that “without a doubt if Iran developed a nuclear bomb, we will follow suit as soon as possible”.

The argument channels the 20th-century theory that owning nuclear weapons acts as a deterrent against enemies using them against you.

The argument channels the 20th-century theory that owning nuclear weapons acts as a deterrent against enemies using them against you.

Deterrence theory has many critics, because it is impossible to prove that it actually works.

One thing that is irrefutable, however, is that nuclear-armed nations – or those believed to be – are still attacked with conventional weapons. Iraq lobbing scuds at Israel in 1991 – or the attacks on the World Trade Center in 2001 – are just two examples.

But developing nuclear weapons in the name of “deterrence” has an even greater potential downside for Middle East nations, say experts, because it sets them up to become pawns in a potential superpower nuclear proxy fight.

“The greater likelihood of tactical exchange if the worst happens between Iran and Saudi would not necessarily be a function of problems between those two nations,” Dorfman noted. “It would be more likely to be a proxy war, a proxy exchange associated with Russia on the one hand and America on the other – both of whom would be happier to sacrifice Gulf States than their own.”

Pressmediaofindia

Pressmediaofindia