05-03-2021

BAGHDAD: Pope Francis began a historic visit to Iraq on Friday, the first by a pontiff to the birthplace of the Eastern Churches from where more than a million Christians have fled over the past 20 years.

An Alitalia plane carrying the pontiff and his entourage, including about 75 journalists, arrived in the Iraqi capital Baghdad on Friday at about 2pm local time amid tight security.

An Alitalia plane carrying the pontiff and his entourage, including about 75 journalists, arrived in the Iraqi capital Baghdad on Friday at about 2pm local time amid tight security.

“This is an emblematic trip and it is a duty towards a land that has been martyred for so many years,” Francis said in brief comments to reporters aboard his plane.

The visit of the pope has a highly symbolic value given the importance of Iraqi Christians in the history of the faith and their cultural and linguistic legacy dating back to the time of ancient Babylon, nearly 4,000 years ago.

The systematic persecution of Iraqi Christians at the hands of al-Qaeda first and then ISIL (ISIS) in more recent years has pushed tens of thousands into diaspora and is threatening the community’s survival.

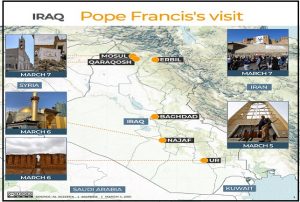

Francis will meet the dwindling Christian communities of Baghdad, Mosul and Qaraqosh, Iraq’s largest Christian city in the Nineveh Plains, where, in 2014, the ISIL armed group wiped out the remnants of the Christian presence  that had survived al-Qaeda’s violent campaigns, causing tens of thousands to flee and find refuge in the autonomous Kurdish region of northern Iraq, Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan.

that had survived al-Qaeda’s violent campaigns, causing tens of thousands to flee and find refuge in the autonomous Kurdish region of northern Iraq, Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan.

In Erbil, the pope will meet the Kurdish authorities and some of the 150,000 Christian refugees from central Iraq that have found shelter there.

“We hope the visit of the pope will bring some attention to the tragedy of Christians in the East and encourage them to stay,” said Cardinal Louis Raphael Sako, the Iraq-born patriarch of the Chaldean Church, in a news conference on Wednesday.

“It will also bring a message of fraternity to the other Iraqi faiths that religion should not divide but unite and that we are all Iraqis and equal citizens.”

Beginning of diaspora

Before the US-led invasion of 2003, Christians of different denominations numbered about 1.6 million in Iraq. Today, less than 300,000 remain, according to figures provided by the Chaldean Church. Since then 58 churches have been damaged or destroyed and hundreds of Iraqi Christians have been killed for their faith.

Under dictator Saddam Hussein, the Christian communities were tolerated and did not face significant security threats, although they were discriminated against.

Under dictator Saddam Hussein, the Christian communities were tolerated and did not face significant security threats, although they were discriminated against.

The diaspora started after the 2003 US-led invasion and the chaos that ensued when al-Qaeda initiated a campaign of targeted assassinations and kidnappings of priests and bishops, and attacks against churches and Christian gatherings.

In October 2006, an orthodox priest, Boulos Iskander, was beheaded and in 2008 the group kidnapped and killed Archbishop Paulos Farah Rahho in Mosul. The same year, another priest and three worshippers were killed inside a church.

In 2010, 48 worshippers were killed in a Syro-Catholic cathedral in Baghdad, where the pope will hold a public meeting on Friday. In 2014, as ISIL occupied Mosul and the Nineveh Plains, the group destroyed more than 30 churches, while the remaining buildings were used as administrative centres, tribunals or prisons, many of which were later bombed as the US-led coalition fought ISIL.

Upon its arrival in Mosul, ISIL asked Christians to convert to Islam, pay a tax or be decapitated, thousands fled to the semi-autonomous Kurdish region and neighboring countries.

Upon its arrival in Mosul, ISIL asked Christians to convert to Islam, pay a tax or be decapitated, thousands fled to the semi-autonomous Kurdish region and neighboring countries.

“When ISIS arrived people had only seconds to gather their things and flee,” Father Karam Shamasha, the reverend of the St George Chaldean Church of Telskuf in Nineveh, told media.

Initially, Christians in the Nineveh villages sheltered other Christians, Yazidis and Shia Muslims fleeing from ISIL, until the group swept through the plains and Christians abandoned their homes. ISIL lost its territory in 2017, but since then few Christians have returned.

“The security situation is not as bad as before, but it is difficult for people to return,” said Father Karam. Only one-third of the 1,450 Christian families of Telskuf have gone back, he said. In Mosul where Christians numbered 50,000 before 2003, only about 150 people have returned.

“Iraqi Christians have been the silent victims of the war. They have felt abandoned,” said Father Karam. “With few exceptions, European countries have not given them asylum, they have not been acknowledged as refugees. This is one of the biggest wounds,” he said.

“Iraqi Christians have been the silent victims of the war. They have felt abandoned,” said Father Karam. “With few exceptions, European countries have not given them asylum, they have not been acknowledged as refugees. This is one of the biggest wounds,” he said.

Interfaith dialogue

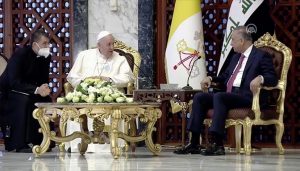

The pope will meet Iraqi President Barham Salih and officials in Baghdad, where he is expected to raise concerns about the discrimination and intimidation faced by Christians.

The pope, who in 2019 inaugurated a new phase of interfaith dialogue between the Roman Church and Islam, will also visit Najaf to meet Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, the highest Shia authority in Iraq, where Shia Muslims represent about 70 percent of the total population.

Representatives of other faiths and Iraq’s minority groups, including Sunni Muslims and Yazidis, are expected to attend an inter-religious meeting with  the pope in Ur, in southern Iraq, which is widely considered the birthplace of Patriarch Abraham, the father of the three monotheistic faiths.

the pope in Ur, in southern Iraq, which is widely considered the birthplace of Patriarch Abraham, the father of the three monotheistic faiths.

“The visit has been hailed by all parties in Iraq as a symbol of the country opening a new page,” said Professor Nahro Zagros, an Iraqi political analyst in Erbil. “But there is a complex reality on the ground and I am afraid it will change little for Christians and other minorities.”

In Mosul, Francis will find what remains of ancient churches and holy shrines, which have been destroyed and desecrated, their artefacts looted or damaged.

The Iraqi authorities accelerated the removal of debris from Mosul’s roads and its Old City, where Francis is expected to pray for the victims of the war at the Hosh al-Bieaa, the Church Square. The area hosted four churches belonging to different Christian denominations, some dating back to the 12th century, none of which was spared by the war.

Meanwhile, the pace of reconstruction in minority neighborhoods in Mosul has been extremely slow.

Meanwhile, the pace of reconstruction in minority neighborhoods in Mosul has been extremely slow.

“The government has done nothing for us, or for other Iraqis, for that matter,” said Father Karam. “People don’t have a house to return to and without a job or the prospect of economic recovery; it is difficult that Christians will ever return.”

Economic hardship and insecurity

Declining oil prices combined with mismanagement, corruption and an unfavorable business environment are deepening Iraq’s economic crisis, according to the World Bank. High unemployment rates and the coronavirus pandemic are putting 12 million people at risk of poverty but it is not only the economic hardship that makes it difficult for Christians to return. The security situation is fragile and minorities feel no longer safe in Iraq.

The Nineveh Plain is under the military control of Shia militias, while ISIL is still operational across the country. In January, ISIL conducted two suicide attacks in Baghdad killing 32 people, the first such big attack since the group lost its so-called caliphate in 2017.

The Nineveh Plain is under the military control of Shia militias, while ISIL is still operational across the country. In January, ISIL conducted two suicide attacks in Baghdad killing 32 people, the first such big attack since the group lost its so-called caliphate in 2017.

Christians have found relative calm in the Kurdish region. Thousands fleeing central Iraq settled there, building schools and churches. Some 150,000 are believed to be living in the region, where, in 2015, the Chaldean Church founded the Catholic University of Erbil, an institute open to students and refugees of all faiths.

Christianity in Iraq dates back to the first century AD when Apostle Thomas preached the gospel in the Mesopotamian region. Iraqi Christians speak classical Syriac, an Aramaic language used for the liturgies but also as a spoken language. Aramaic dates back to the 10th century BC, making it the world’s oldest recorded living language.

Several Aramaic languages, considered endangered, have survived within Christian communities in the Near East mainly used by the older generations. The diaspora of Christian communities means they could become extinct in the near future. (Int’l News Desk)

Pressmediaofindia

Pressmediaofindia