02-02-2025

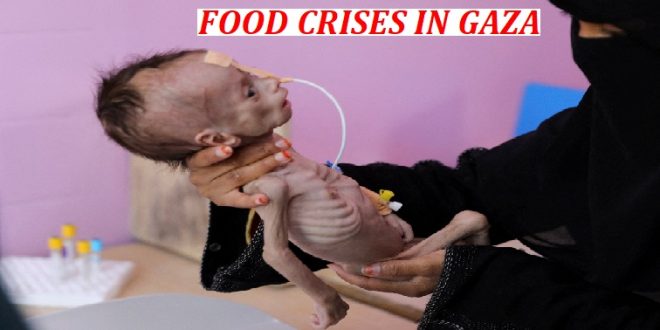

GAZA CITY/ LONDON: A surge in the flow of aid into the Gaza Strip since the truce between Israel and Hamas took effect on Jan. 19 is likely to ease the acute food emergency afflicting people in the war-ravaged territory, especially its children but even after relief reaches them, the hunger they have endured could cast a shadow over their health for years to come.

More than 60,000 children in Gaza will need treatment for acute malnutrition in 2025, according to United Nations estimates from Jan. 22. Some have already died estimates of how many vary widely. Survivors who are able to return to adequate levels of nutrition nonetheless face an insidious threat; the multiple long-term health problems linked to childhood malnutrition.

More than 60,000 children in Gaza will need treatment for acute malnutrition in 2025, according to United Nations estimates from Jan. 22. Some have already died estimates of how many vary widely. Survivors who are able to return to adequate levels of nutrition nonetheless face an insidious threat; the multiple long-term health problems linked to childhood malnutrition.

This troubling prospect is of urgent global concern. As Reuters has reported in a series of articles, famine and other acute food crises have ravaged populations across the developing world over the past year, from Haiti to Afghanistan to Sudan and many other African nations, as well as Gaza.

About 131 million children, nearly 40 million of them under age 5, live in areas experiencing acute food crises around the world, according to estimates provided exclusively to Reuters by the United Nations’ World Food Program. Nearly 4.7 million pregnant women live in these areas, the United Nations Population Fund said. The UN estimates are based on the most recent data from countries where assessments were possible.

The lasting damage of childhood hunger is wide-ranging and can be profound, according to scientists, nutrition experts and officials at humanitarian organizations. Children who experience severe malnutrition may never reach their full cognitive or physical potential, according to multiple studies that have tracked survivors of past food shortages. Other studies have shown that undernutrition in childhood, and even in the womb, can be associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and other non-communicable illnesses later in life.

“People focus, quite rightly, on the short-term aspects of malnutrition,” said Marko Kerac, professor of nutrition for global health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. “What’s missed … is that the damage done will not suddenly stop when the emergency stops.”

“People focus, quite rightly, on the short-term aspects of malnutrition,” said Marko Kerac, professor of nutrition for global health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. “What’s missed … is that the damage done will not suddenly stop when the emergency stops.”

Studies have shown that some effects of severe hunger can be mitigated if a child later gains access to good nutrition. But that is a big if. In many countries where food crises occur, poverty, war and civil strife persist long after the crisis has passed, limiting children’s access to adequate food and healthcare.

That makes it hard to get exact data on how many are affected in both the short and long-term, said Hannah Stephenson, head of nutrition with Save the Children but “the more severely malnourished a child is, the harder it will be to recover,” she said. The duration of malnourishment is also a crucial variable, she said.

She and other experts stressed that while every malnourished child is a tragedy, famines and other food crises can do lasting harm to society as whole by leaving an entire generation with physical and cognitive deficits. “It costs the person, the family, the country,” said Professor Mubarek Abera, a child and maternal nutrition and mental health researcher at Jimma University in Ethiopia who was born during that country’s famine in the early 1980s.

In a food crisis, children are more vulnerable than adults to malnourishment and death from starvation or infectious diseases, which are more lethal to those weakened by hunger. (Int’l Monitoring Desk)

Pressmediaofindia

Pressmediaofindia