06-12-2024

SANTIAGO NILTEPEC, MEXICO: Carlos Perez, a 30-year-old Colombian migrant from Bogota, was on track to reach the United States border with his wife and 11-year-old son by the New Year.

The trouble came, however, when his wife became overwhelmed with fatigue as they reached the city of Tapachula in southern Mexico. By that point, they had travelled 2,500km more than 1,550 miles on foot.

So, Perez bought a bicycle. Often, he pedalled while his wife and child sat on the handlebars. On treacherous roads and at night, Perez walked alongside them as they rode slowly through darkness but a road accident in mid-November tore the skin from his shins and bloodied his wife and son’s arms.

So, Perez bought a bicycle. Often, he pedalled while his wife and child sat on the handlebars. On treacherous roads and at night, Perez walked alongside them as they rode slowly through darkness but a road accident in mid-November tore the skin from his shins and bloodied his wife and son’s arms.

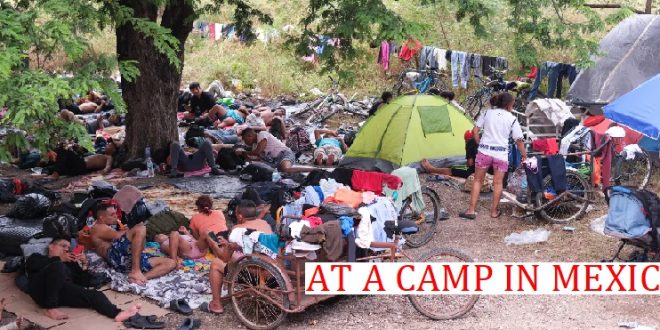

Speaking a day later from a temporary migrant camp in Santiago Niltepec, Perez expressed a fear that their injuries will cost them the chance to cross into the US before President-elect Donald Trump takes office on January 20, 2025.

“I don’t know if it’s possible to reach the border in time now,” Perez said.

Like many of his fellow migrants and asylum seekers, Perez fears that Trump will follow through on his pledges to “close” the US border with Mexico.

Trump, a Republican, has teased that his incoming administration plans to declare a national emergency and deploy military forces to prevent unauthorised crossings, which he likens to an “invasion”.

Already, Trump has claimed that early negotiations with Mexico to crack down on migrants and asylum seekers have borne fruit.

“Mexico will stop people from going to our Southern Border, effective immediately,” Trump wrote on social media on November 27. “THIS WILL GO A LONG WAY TOWARD STOPPING THE ILLEGAL INVASION OF THE USA.”

Still, it is unclear whether his hard-knuckle rhetoric will help stem the flow of people coming to the US or fuel it in the lead-up to his inauguration.

As blood soaked into his fresh bandage, Perez indicated that he had not yet given up hope of reaching the border. His eyes flitted to the closed white curtains of a mobile clinic set up by Doctors Without Borders (MSF).

As blood soaked into his fresh bandage, Perez indicated that he had not yet given up hope of reaching the border. His eyes flitted to the closed white curtains of a mobile clinic set up by Doctors Without Borders (MSF).

“My son is inside. They are cleaning and bandaging his body. We can only wait to see if we can heal in time to make it,” he said.

He told Al Jazeera that his family fled gang warfare and extortion in their home city. Others in the camp had escaped poverty, death threats and instability.

One man, Omar Ramirez, described fleeing political persecution under President Nicolas Maduro of Venezuela.

Ramirez, who is in his forties, was a well-respected digital journalist in the country but at the camp, insects crawl in and out of the open sores on his feet.

Clutched closely to his chest is an A4 plastic folder containing scanned documents proving his address, university degree and Venezuelan bank accounts paperwork he hopes to use to apply for asylum in the US.

Among the sheets are his press pass for the 2007 Copa America football tournament and a blown-up photo of him smiling broadly next to a 19-year-old Lionel Messi but in the months since Venezuela’s contested presidential election in July, Ramirez explained that he stopped feeling safe in his home country. Maduro has sought to stifle questions about his re-election by detaining journalists and activists, according to human rights monitors.

“I was an outspoken critic of Maduro,” Ramirez said. “And I supported those who opposed him.” (Al Jazeera)

Pressmediaofindia

Pressmediaofindia