03-09-2024

BARCELONA, SPAIN: The morning he turned 18, the Spanish children’s centre that Ilyas* (name has been changed) had been sheltering in for two years since he arrived across the border from Morocco unceremoniously kicked him out.

He wasn’t even permitted to stay for breakfast.

Now that he was an adult, the authorities said; he was on his own.

That was on January 30 this year and Ilyas who doesn’t like to go by his real first name because of the shame he feels at being unemployed and homeless left the centre for unaccompanied minors in the Spanish Ceuta enclave on the northern tip of Morocco and headed out in search of some other way to survive.

That was on January 30 this year and Ilyas who doesn’t like to go by his real first name because of the shame he feels at being unemployed and homeless left the centre for unaccompanied minors in the Spanish Ceuta enclave on the northern tip of Morocco and headed out in search of some other way to survive.

The small amount of pocket money a social worker gave him before he left Ceuta’s migrant minors’ centre paid for the ferry to the Spanish mainland port of Algeciras. There, he was approached by local social workers who recommended he travel 98km (61 miles) up to the city of Jerez where a place in a facility for young migrants was vacant, they said.

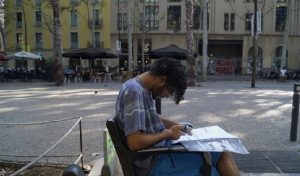

Six months later, Ilyas finally reached Barcelona where he still hopes to find work not just to support himself, but to help his sick father and family back home but it hasn’t been an easy journey across Spain.

One month after arriving in Jerez, the facility staff told him he could not stay any more. That led to living on the streets for several months while he scoured fruitlessly for job opportunities nobody there wanted to employ a teenage boy from Morocco.

He finally decided to travel north to the more multicultural Barcelona in the hopes of finding a more sympathetic setting but, now, Ilyas is broken after weeks of sleeping rough here too.

“I am tired of life. I hope, for once, something works out well for me,” he sobs as he steels himself in the morning for another day of searching for somewhere he might have a shower and change his dirty clothes before he goes to ask social services for a place to sleep tonight.

Ilyas has been sleeping rough for months now.

Despite all of it, though, Ilyas says he does not regret leaving his hometown of Fnideq in Morocco, close to the Spanish border, when he was only 15. “Living on the street is better than living under my parents’ roof knowing that I have no future,” he says.

Despite all of it, though, Ilyas says he does not regret leaving his hometown of Fnideq in Morocco, close to the Spanish border, when he was only 15. “Living on the street is better than living under my parents’ roof knowing that I have no future,” he says.

Children and young men living in Morocco’s northern cities at the brink of economic collapse, he says, are born with a desire to migrate “inserted into their hearts”.

Fnideq and other border towns have been suffering particularly since Spain closed the border during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and then never renewed the permissions for people to cross daily into Ceuta to work, the main source of local employment for thousands of people in his hometown.

“From the second we are born, we know we need to leave this place.”

‘The worst night of my life’

At the same hour of the day, Ilyas’s mother, Aseya, 42, is partway through her shift as a cleaner at a restaurant by the sea in Fnideq. She is the holder of one of the remaining few jobs in the town. Aseya works 14 hours every day from 6am to 8pm for a salary of just 100 dirhams ($10.24).

Ilyas’s four siblings Boushra, 17, Zakarya, 12, Adam, 11, and Chaymaa, 8, sit at one of the restaurant tables for hours waiting for their mother to finish work.

They have little else to do. Boushra, the eldest since Ilyas left, takes care of the younger ones while Aseya is in the kitchen.

Next year, she will finish high school and dreams of studying engineering in nearby Tetouan. It’s an unlikely dream, however, because of the cost it would involve. (Int’l Monitoring Desk)

Pressmediaofindia

Pressmediaofindia