05-07-2025

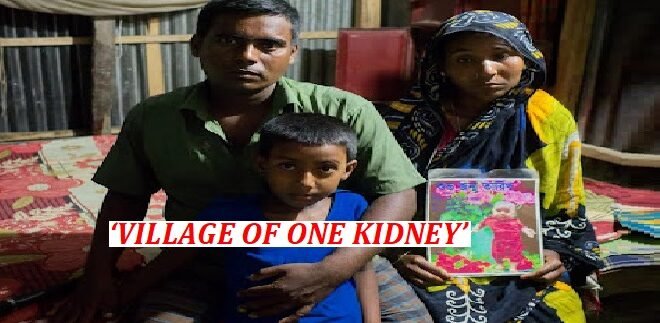

KOLKATA, NEW DELHI/ JOYPURHAT, DHAKA: Under the mild afternoon sun, 45-year-old Safiruddin sits outside his incomplete brick-walled house in Baiguni village of Kalai Upazila in Bangladesh, nursing a dull ache in his side.

In the summer of 2024, he sold his kidney in India for 3.5 lakh taka ($2,900), hoping to lift his family out of poverty and build a house for his three children, two daughters, aged five and seven and an older 10-year-old son. That money is long gone, the house remains unfinished and the pain in his body is a constant reminder of the price he paid.

In the summer of 2024, he sold his kidney in India for 3.5 lakh taka ($2,900), hoping to lift his family out of poverty and build a house for his three children, two daughters, aged five and seven and an older 10-year-old son. That money is long gone, the house remains unfinished and the pain in his body is a constant reminder of the price he paid.

He now toils as a daily laborer in a cold storage facility, as his health deteriorates, the constant pain and fatigue make it hard for him to carry out even routine tasks.

“I gave my kidney so my family could have a better life. I did everything for my wife and children,” he said.

At the time, it didn’t seem like a dangerous choice. The brokers who approached him made it sound simple, an opportunity rather than a risk. He was sceptical initially but desperation eventually won over his doubts.

The brokers took him to India on a medical visa, with all arrangements, flights, documents and hospital formalities handled entirely by them. Once in India, although he travelled on his original Bangladeshi passport, other documents, such as certificates falsely showing a familial relationship with the intended recipient of his kidney, were forged.

His identity was altered and his kidney was transplanted into an unknown recipient whom he had never met. “I don’t know who got my kidney. They (the brokers) didn’t tell me anything,” Safiruddin said.

By law, organ donations in India are only permitted between close relatives or with special government approval but traffickers manipulate everything, family trees, hospital records, even DNA tests, to bypass regulations.

“Typically, the seller’s name is changed and a notary certificate, stamped by a lawyer is produced to falsely establish a familial relationship with the recipient. Forged national IDs support the claim, making it appear as though the donor is a relative, such as a sister, daughter or another family member, donating an organ out of compassion,” said Monir Moniruzzaman, a Michigan State University professor and a member of the World Health Organization’s Task Force on Organ Transplantation, who is researching organ trafficking in South Asia.

“Typically, the seller’s name is changed and a notary certificate, stamped by a lawyer is produced to falsely establish a familial relationship with the recipient. Forged national IDs support the claim, making it appear as though the donor is a relative, such as a sister, daughter or another family member, donating an organ out of compassion,” said Monir Moniruzzaman, a Michigan State University professor and a member of the World Health Organization’s Task Force on Organ Transplantation, who is researching organ trafficking in South Asia.

Safiruddin’s story isn’t unique. Kidney donations are so common in his village of Baiguni, that locals know the community of less than 6,000 people as the “village of one kidney”. The Kalai Upazila region that Baiguni belongs to is the hotspot for the kidney trade industry; a 2023 study published in the British Medical Journal Global Health publication estimated one in 35 adults in the region has sold a kidney.

Kalai Upazila is one of Bangladesh’s poorest regions. Most donors are men in their early 30s lured by the promise of quick money. According to the study, 83 percent of those surveyed cited poverty as the main reason for selling a kidney, while others pointed to loan repayments, drug addiction or gambling.

Safiruddin said that the brokers who had taken his passport, never returned it. He didn’t even get the medicines he had been prescribed after the surgery. “They (the brokers) took everything.”

Brokers often confiscate passports and medical prescriptions after the surgery, erasing any trail of the transplant and leaving donors without proof of the procedure or access to follow-up care. (Al Jazeera)

Pressmediaofindia

Pressmediaofindia