08-06-2025

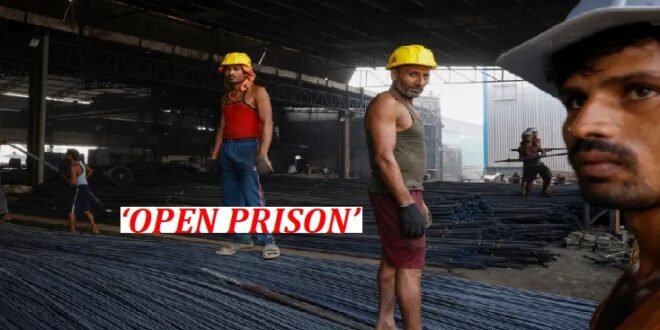

NEW DELHI: Amid the relentless clatter of machinery, Ravi Kumar Gupta feeds a roaring steel furnace with scrap, blown metal and molten iron. He carefully adds chemicals tailored to the type of steel being produced, adjusting fuel and airflow with precision to keep the furnace running smoothly.

As his shift ends about 4pm, he stops briefly at a roadside tea shop just outside the gates of the steel factory in Maharashtra state’s Tarapur Industrial Area. His safety helmet is still on, but his feet, instead of being shielded by boots, are in worn-out slippers, scant protection against the molten metal he works with. His eyes are bloodshot with exhaustion, and his green, full-sleeved shirt and faded, torn blue jeans are stained with grease and sweat.

As his shift ends about 4pm, he stops briefly at a roadside tea shop just outside the gates of the steel factory in Maharashtra state’s Tarapur Industrial Area. His safety helmet is still on, but his feet, instead of being shielded by boots, are in worn-out slippers, scant protection against the molten metal he works with. His eyes are bloodshot with exhaustion, and his green, full-sleeved shirt and faded, torn blue jeans are stained with grease and sweat.

Four years after migrating from Barabanki, a district in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, Ravi earns $175 per month, $25 less than India’s monthly per capita income. And the paycheques are often delayed, arriving only between the 10th and 12th of each month.

Middlemen, who are either locals or long-term migrants posing as locals, supply labour to factories in Maharashtra, India’s industrial heartland. In return, the middlemen skim between $11 and $17 from each worker’s wages. In addition, $7 is deducted monthly from their pay for canteen food, which consists of limited portions of rice, dal and vegetables for lunch, as well as evening tea.

Asked why he continues to work at the steel factory, Ravi responds with resignation in his voice: “What else can I do?”

Giving up his job isn’t an option. His family, two young daughters in school, his wife and mother who work on their small plot of farmland, and his ailing father who is unable to work, depend on the $100 a month that he is able to send home. Climate change, he says, has “ruined farming”, the family’s traditional occupation.

“The rains don’t come when they should. The land no longer feeds us and where are the jobs in our village? There’s nothing left. So, like the others, I left,” he says, his thick, calloused hands wrapped around a cup of tea.

Ravi is a cog in the wheel of the soaring dreams of the world’s fifth-largest economy. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has boldly spoken of making India a $5 trillion economy, up from $3.5 trillion in 2023 but as Modi’s government woos global investors and assures them that it is easy today to do business in India, Ravi is among millions of workers whose stories of withheld wages, endless toil and coercion, telltale signs of forced labour, according to the United Nations’ International Labour Organization (ILO), provide a haunting snapshot of the ugly underbelly of the country’s economy.

Ravi is a cog in the wheel of the soaring dreams of the world’s fifth-largest economy. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has boldly spoken of making India a $5 trillion economy, up from $3.5 trillion in 2023 but as Modi’s government woos global investors and assures them that it is easy today to do business in India, Ravi is among millions of workers whose stories of withheld wages, endless toil and coercion, telltale signs of forced labour, according to the United Nations’ International Labour Organization (ILO), provide a haunting snapshot of the ugly underbelly of the country’s economy.

The Factories Act of 1948, which governs working conditions in steel mills like the one where Ravi works, mandates annual paid leave for workers who have been employed for 240 days or more in a year. However, workers like Ravi do not receive paid leave. Any day taken off is unpaid, regardless of the reason.

Like many others, Ravi is required to work all seven days a week, totaling 30 days a month, despite the fact that Sundays were officially declared a weekly holiday for all labourers in India as far back as 1890.

Workers in many Indian factories do not receive a salary slip detailing their earnings and deductions. This lack of transparency leaves them in the dark about how much money has been deducted or why.

Worse still, if a worker is absent for three or four consecutive days, their entry card is deactivated. Upon returning, they are treated as a new employee. This reclassification affects their eligibility for important benefits such as the provident fund and end-of-service gratuity. (Al-Jazeera)

Pressmediaofindia

Pressmediaofindia