08-06-2025

MIAMI MUMBAI: Twenty-two years ago, when Erna stood outside her house, “the windows were as high as my chest”. Now they’re knee-height.

As their home has sunk, she and her family have had to cope with frequent flooding. In the most extreme cases “we used canoes – the water kept coming in and swamped the ground floor”, she says.

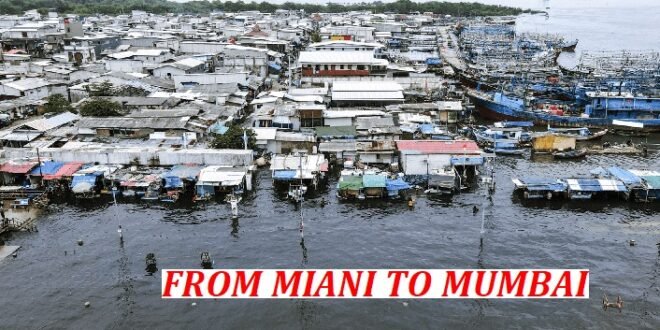

Erna lives in the Indonesian capital Jakarta – one of the fastest-sinking cities in the world. Her home is in one of the worst-affected areas, the north of the city, and is now much lower than the road.

Erna lives in the Indonesian capital Jakarta – one of the fastest-sinking cities in the world. Her home is in one of the worst-affected areas, the north of the city, and is now much lower than the road.

The 37-year-old grew up here and remembers playing in nearby streets and praying in the mosque, that is now long gone, permanently underwater, as is the old port.

The walls of her home, built in the 1970s, are cracked, and you can see where thick layers of concrete have been added to the floor to try to restore it to ground level – about 10 times since it was built, and a metre thick in some places. The house is still subsiding, and Erna can’t afford to move.

This is one of dozens of coastal regions that are sinking at a worrying speed, according to a study by Nanyang Technological University (NTU) in Singapore.

The team studied subsidence in and around 48 coastal cities in Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas. These are places that are particularly vulnerable to a combination of rising sea levels, which are mainly driven by climate change, and sinking land.

Based on the study and population data from the United Nations, the BBC estimates that nearly 76 million people live in parts of these cities that subsided, on average, at least 1cm per year between 2014 and 2020.

The impact on their lives can be huge – for example in Tianjin in north-east China, 3,000 people were evacuated from high-rise apartment buildings in 2023, after subsidence left large cracks in nearby streets.

All 48 urban areas in the NTU study are shown in this globe. The most extreme cases of subsidence were seen in Tianjin, which has undergone rapid industrial and infrastructural development this century. The worst-hit parts of the city sank up to 18.7cm per year between 2014 and 2020.

Select a city below to see how much it is sinking by. A map will display the most subsiding areas in that city in green, with details of factors contributing to subsidence.

Select a city below to see how much it is sinking by. A map will display the most subsiding areas in that city in green, with details of factors contributing to subsidence.

The subsidence rate is measured from a reference point in each city, which scientists assume is more stable than others – you can read more on the methodology at the end of this article.

The perils of groundwater pumping

Many factors can contribute to subsidence, including building, mining, tectonic shifts, earthquakes, and natural soil consolidation – where soil is pressed closer and becomes more dense over time but “one of the most common causes is groundwater extraction”, explains the lead researcher on the NTU study, Cheryl Tay. It has had a major impact in half of the 48 coastal cities identified in the study.

Groundwater is found beneath the Earth’s surface in cracks and spaces in sand, soil and rock.

It makes up about half of the water used for domestic purposes – including drinking – around the world. It’s also essential for irrigating crops but as cities grow, freshwater supplies come under strain. Households and industries in some places drill their own wells or boreholes and extract too much – as in Jakarta.

Extracting excessive amounts of water in this way over extended periods of time compresses the soil, eventually causing the surface – and everything built on it – to sink or subside.

Pressmediaofindia

Pressmediaofindia