22-01-2026

DHAKA: For most of his adult life, Rafiul Alam did not believe that voting was worth the walk to the polling station. He is 27, grew up in a middle-class neighborhood of Dhaka, and became eligible to vote nearly a decade ago. He never did, not in Bangladesh’s national elections in 2018, nor in the 2024 vote.

“My vote had no real value,” he said.

“My vote had no real value,” he said.

Like many Bangladeshis in his age group, Alam’s political consciousness formed under former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s long period of government, when opposition parties and election watchdogs repeatedly questioned the credibility of polls.

Over time, he said, disengagement with politics became normal, even rational, for a generation. “You grow up knowing elections exist, but believing they actually don’t have the power to decide anything. So you put your energy elsewhere… studies, work, even trying to leave the country,” he said.

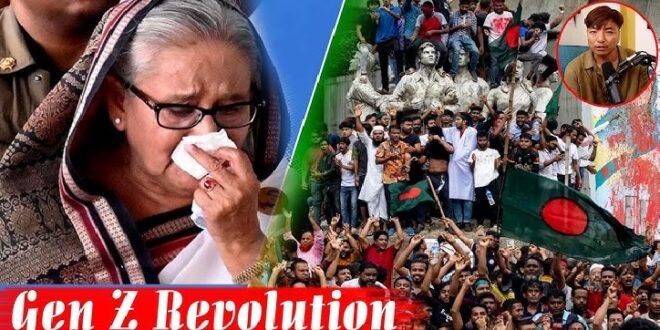

This calculation began to shift for him in July 2024, when student protests over a government job reservation system favoring certain groups spiraled into a nationwide uprising. Alam joined marches in Dhaka’s Mirpur area and helped coordinate logistics for protests, as Hasina’s security forces launched a brutal crackdown.

The United Nations Human Rights Office later estimated that up to 1,400 people most of them young, may have been killed before Hasina fled to India on August 5, 2024, ending nearly 15 years in power.

When Hasina left, Alam said the moment felt like something that had appeared permanent had broken. “For the first time, it felt like ordinary people could push for a change,” he said. “Once you experience that, you feel responsible for what comes next.”

Bangladesh is now heading for a national election on February 12, the first since the uprising. European Union observers have described the upcoming vote as the “biggest democratic process in 2026, anywhere” and Alam plans to vote for the first time.

“I’m thrilled to exercise my lost right as a citizen,” he said.

He is not alone. Bangladesh has about 127 million registered voters, nearly 56 million of them between the ages of 18 and 37, according to the Election Commission. They constitute about 44 percent of the electorate, and are a demographic widely seen as the driving force behind Hasina’s downfall.

“Practically speaking, anyone who turned 18 after the 2008 parliamentary election has never had the chance to vote in a competitive poll,” said Humayun Kabir, director general of the Election Commission’s national identity registration wing.

“Practically speaking, anyone who turned 18 after the 2008 parliamentary election has never had the chance to vote in a competitive poll,” said Humayun Kabir, director general of the Election Commission’s national identity registration wing.

“That means people who have been unable to vote for the last 17 years are now in their mid-30s… and especially eager to cast their ballots.”

This eagerness comes after three post-2008 elections that “were not considered credible”, Ivars Ijabs, the EU’s chief observer, said.

The 2014 polls saw a mass opposition boycott, and dozens of seats where Hasina’s Awami League party faced no contest. The 2018 vote, though contested, became widely known as the “night’s vote”, after allegations that ballot boxes had been filled before polling day.

The 2024 election, meanwhile, again went ahead amid a major boycott by opposition parties, with critics arguing that conditions for a “fair contest did not exist”.

Fragmented by class, geography, religion and experience, Bangladesh’s young voters are united less by ideology than by a shared suspicion of institutions, which, for most of their adult lives, have failed to represent them, say analysts. (Int’l News Desk)

Pressmediaofindia

Pressmediaofindia