25-04-2021

By SJA Jafri + Bureau Report

CANBERRA/ MELBOURNE: “ANZAC Day” is a national day of remembrance in Australia and New Zealand that broadly commemorates all Australians and New Zealanders “who served and died in all wars, conflicts, and peacekeeping operations” and “the contribution and suffering of all those who have served”. Observed on 25 April each year, Anzac Day was originally devised to honor the members of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) who served in the Gallipoli Campaign, their first engagement in the First World War (1914 – 1918).

Most of Australians did not mark ANZAC Day every years even the majority does not even know ‘what is ANZAC Day while some remember it and organize programs according to their capacities hence, it is has been observing officially annually but because of coronavirus pandemic, this year, no remarkable program or event organized across the country because the “ANZAC Day” reveals the continuous 100 years blenders and crimes of Australia, sources told PMI.

Bob Manz was 19 years old when, in 1967, he received his conscription notice for service in the Australian Army during the Vietnam War.

Bob Manz was 19 years old when, in 1967, he received his conscription notice for service in the Australian Army during the Vietnam War.

“I was about to turn 20,” he told media. “It didn’t seem real to me, it never felt real to me that I could finish up in Vietnam with bullets flying around.”

In 1964, the Australian government had committed to sending troops to Vietnam in support of the United States while on a trip to the White House, then-Prime Minster Harold Holt said his nation would go “all the way with LBJ (Lyndon B Johnson)” even if it meant conscripting young men like Bob in to “national service”.

Yet Bob and many young men like him would take the dramatic step of becoming a draft resister; someone who was required to join the army for service by law, but would actively refuse to do so.

“When I became a draft resister I was doing so on the basis that I wanted to do all I could to hinder the Australian government’s participation in the war on the basis it was an unjust war,” he said.

Bobbie Oliver, a lecturer at the University of Western Australia, is currently researching and writing a book on conscientious objectors and draft resisters.

Her research has revealed that between 1961 and 1972, more than 60,000 Australians served in the Vietnam War, a third of them conscripts.

Of the 521 Australians to die in action, nearly half were people drafted into the military but conscription was also met fierce resistance.

Oliver said conscription was unpopular because it had not been secured with the consent of the public or Parliament.

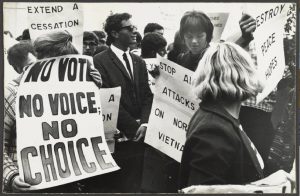

“When national service was brought back in in 1964, it very quickly became that the option was to send conscripts to Vietnam,” she told media, noting opposition to the draft was also influenced by the protest movement in the US.

“When national service was brought back in in 1964, it very quickly became that the option was to send conscripts to Vietnam,” she told media, noting opposition to the draft was also influenced by the protest movement in the US.

“There was no referendum. It wasn’t agreed by both sides of Parliament or anything. It was just announced that this would happen. That’s one of the reasons there was so strong an objection to that national service scheme.”

An ‘undeclared war’

April 25 marks ANZAC Day in Australia and New Zealand, when people in both countries remember the various conflicts their troops have been involved in, often in partnership New Zealand also sent troops to Vietnam, albeit not conscripts but while the day highlights the sacrifice and personal commitment of those who went to war, little is acknowledged of those people who objected to such conflicts, often at considerable personal cost.

Oliver said those who refused to serve would initially apply for conscientious objector status, which meant going to court and proving a strict adherence to pacifism, usually on religious grounds.

However, she said that “by about 1967 and 1968, there were a lot more people just refusing to comply.”

“Many did not object on Christian grounds or any form of religious grounds many objected specifically to the Vietnam War which was an undeclared war,” she said.

For young men who would become either draft resisters or conscientious objectors, the penalty for failing to comply with the military draft or failing to prove outright pacifism could be harsh including lengthy prison sentences in either military or civilian jails.

Teacher William “Bill” White was one of the first publicly known resisters, when in 1966, his application for conscientious objector status was denied by the courts.

Teacher William “Bill” White was one of the first publicly known resisters, when in 1966, his application for conscientious objector status was denied by the courts.

After he refused to heed further call up notices, he was dragged from his home by police and imprisoned.

In 1969, the two-year imprisonment of conscript John Zarb in Melbourne’s notorious Pentridge prison also attracted large protests, with the government eventually releasing him after 10 months.

Oliver said her research reveals “pretty horrific stories in the way they were treated (in prison) kept on bread and water, woken up every hour and at night, told to stand up and give their name, rank and number.”

Excluded, harassed

Such penalties – along with social and familial exclusion, and harassment meant that some conscientious objectors and draft resistors were left with psychological scars.

“People had experiences of either former work colleagues or relatives who refused to speak to them afterwards,” Oliver said. “Some told me they had been disadvantaged at work and denied promotions.”

After refusing to attend a medical examination, a magistrate sentenced Bob Manz to a week in jail, which he said was to give him a taste of prison should he further non-comply with his conscription.

After being released, Manz went underground after ignoring the final “call up” notice and spent most of 1972 “keeping one step ahead of the police”.

Fortunately, the election of anti-war Prime Minister Gough Whitlam that same year meant the end of both the war and conscription.

It also meant Manz could re-emerge into public life.

“Whitlam won the election on Saturday and by Wednesday, (the conscripts) were out of jail,” he recalled. “And that was it. Normal life. I was free, I could walk around.”

“Whitlam won the election on Saturday and by Wednesday, (the conscripts) were out of jail,” he recalled. “And that was it. Normal life. I was free, I could walk around.”

The Australian War Memorial, which oversees the nation’s military history, has included in its Vietnam War display information about opposition to the war and the role of conscientious objectors.

The Memorial also houses photographs, film, interviews and articles about the protest movement in its archival collection but Bob Manz said more should be done to acknowledge the opposition to the Vietnam War, along with supporting veterans, whether conscripted or not.

Australia’s Prime Minister Scott Morrison recently announced a Royal Commission into veteran suicides including those having served more recently in Iraq and Afghanistan.

At least 400 Australian defence force veterans have died by suicide since 2001 compared with 41 deaths in combat in Afghanistan during the same period.

“The veterans have been done a terrible injustice over the years,” Manz said. “They warrant our understanding and support. And while we are at it, we should re-assert the contributions of the anti-war movement.”

Before ANZAC Day, Bob, now 73 years old, reflected on his role as a draft resister.

He has no regrets.

“I’m still very proud of what I did. I think it was the right thing to do and I’m glad I did it.”

Pressmediaofindia

Pressmediaofindia