13-10-2021

By SJA Jafri +Bureau Report + Agencies

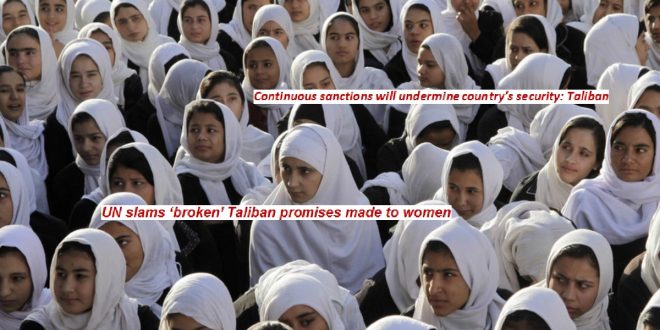

KABUL/ ISLAMABAD: Kabul resident Rahela Nussrat, 17, is in her final year of high school, but she has not been able to attend classes. The reason: Afghanistan’s new rulers have decided to keep teenage girls out of school for now.

KABUL/ ISLAMABAD: Kabul resident Rahela Nussrat, 17, is in her final year of high school, but she has not been able to attend classes. The reason: Afghanistan’s new rulers have decided to keep teenage girls out of school for now.

Last month, the Taliban announced schools would be opening, but only boys of all ages were asked to return to school, leaving out secondary school girls. The move has raised questions about the group’s policy about women’s education.

The Taliban said “a safe learning environment” was needed before older girls could return to school, adding that schools will reopen as “soon as possible”, without giving a timeframe.

“Education is one of the most fundamental human rights, but today, that basic right has been taken from me and millions of other Afghan girls,” Nussrat told media

Afghanistan had struggled to get girls back into school during the Western-backed government of President Ashraf Ghani. According to a 2015 survey (PDF) prepared for UNESCO by the World Education Forum, nearly 50 percent of Afghan schools lacked usable buildings.

More than 2.2 million Afghan girls were unable to attend school as recently as last year, 60  percent of the total children out-of-school in the country.

percent of the total children out-of-school in the country.

The Taliban’s lack of clarity on the reopening of secondary schools has compounded the problem and is a blow to millions of girls, especially those whose families thought the end of the war could return to some semblance of normal life.

“When the Afghan government fell, I lost my right to education, this was the first time I cried specifically because of my gender,” Nussrat said.

She said she still does not understand the reasoning for only keeping teenage girls from education, but she is certain that if it continues, it will only backfire on the Taliban.

“They kept saying they want young people to stay and use their talents, but they’re just driving us all out,” Nussrat said by phone from her Kabul home.

Thousands of young Afghans fled the country after the Taliban returned to power on August 15, 20 years after it was removed from power in a US-led military invasion.

Nussrat viewed herself as an example, saying she is currently preparing for English-language exams so she can apply for study abroad opportunities.

As someone who managed to come from one of the nation’s poorest provinces, Daikundi, where even boys drop out of school as teenagers to start working as day labourers, Nussrat said the Taliban is losing out on entire generations of driven, determined young people.

As someone who managed to come from one of the nation’s poorest provinces, Daikundi, where even boys drop out of school as teenagers to start working as day labourers, Nussrat said the Taliban is losing out on entire generations of driven, determined young people.

“I studied for 14 years in Kabul, I went through primary and secondary school during a war, but now I will have to leave the country,” she said.

“I will apply to universities abroad and some other country will take me and my talents, because they know it’s not possible to study in a Taliban-led Afghanistan.”

The Taliban stance on the education of girls and women has faced criticism from Qatar and Pakistan, which have called on the international community to engage with the Taliban.

At a news conference last month, Qatari Foreign Minister Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al Thani, said it “has been very disappointing to see some steps being taken backwards” by the Taliban, who in the 1990s were the only leaders to ever ban women and girls from education and employment in Afghan history.

Sheikh Mohammed said Qatar, which hosts the Taliban’s political office, should be used as a  model for how a Muslim society can be run. “Our system is an Islamic system [but] we have women outnumbering men in workforces, in government and in higher education.”

model for how a Muslim society can be run. “Our system is an Islamic system [but] we have women outnumbering men in workforces, in government and in higher education.”

Imran Khan, the Pakistani prime minister, said that although he doubted the Taliban would once again place an outright ban on girls’ education, the group should be reminded that Islam would never allow such a thing to happen again.

“The idea that women should not be educated is just not Islamic. It has nothing to do with religion,” Khan told the BBC.

Prior to the Taliban’s arrival, cultural traditions were used as a basis for some families to keep their girls, especially older ones, from school. According to UNICEF, 33 percent of Afghan girls are married before the age of 18.

Aisha Khurram, a grad student of law at Kabul University, said she has little faith the Taliban will allow Afghan women to serve a meaningful role in Afghan society.

Since it came to power, the Taliban has sent mixed signals about women returning to work in government offices and has forced universities to enact policies of gender segregation in order to reopen.

Khurram, a former youth representative to the United Nations, said she saw no need for dividing the genders at Afghanistan’s premier higher education institution.

Khurram, a former youth representative to the United Nations, said she saw no need for dividing the genders at Afghanistan’s premier higher education institution.

“I had always known Kabul University for its inclusive and accommodating environment for female students,” she said.

Though she has a hard time reconciling it with her experiences of education in Afghanistan, Khurram said gender segregation should not be used as an excuse to keep all Afghan women from education as the Taliban did in the 1990s.

Other women Al Jazeera spoke to said though the separation of men and women received a lot of social media attention, it should not be the focus of people who truly wish to see educational opportunities return for men and women in Afghanistan.

Pashtana Durrani, an education advocate who focuses on bringing digital learning tools to rural areas, said that for millions of women across the country, separating the genders is not nearly as big a deal as foreign media and certain residents in Kabul are making it out to be.

“In so many parts of the country, gender segregation is the norm. People are used to it. Even in  Kabul, weddings are separated by gender,” Durrani told media from the southern province of Kandahar.

Kabul, weddings are separated by gender,” Durrani told media from the southern province of Kandahar.

Durrani argued, for many families, gender segregation could be key to them allowing their older girls to study at the university level, saying that even before the Taliban takeover, girls in Kandahar’s public and private universities wore Arab-style abayas and niqabs, “because the boys would be around.”

However, Khurram, the law student, said that although Afghan women have agreed to these new regulations on segregation, the Taliban has failed to live up to their end of the bargain, to open the schools.

“The Taliban’s promises have yet to be proven in their actions. They have yet to accept that Afghanistan has changed,” since the group’s brief five-year rule in the 1990s.

On Monday, the UN chief criticized the Taliban’s “broken” promises to Afghan women and girls, referring to the continued closure of schools.

Durrani said what is most important for Afghan girls and women are that they can study without interference from the Taliban.

“At this point, for these girls, it’s all about education. Even if they get married and have to sit at home after that, they just want the diploma, the piece of paper, to show what they were able to achieve,” Durrani said of the young women she has spoken to in Kandahar.

“At this point, for these girls, it’s all about education. Even if they get married and have to sit at home after that, they just want the diploma, the piece of paper, to show what they were able to achieve,” Durrani said of the young women she has spoken to in Kandahar.

She said even the female principals she has spoken to at three different schools in and around the Kandahar city, are fearful for their future, even though she said everything is in place for all girls to return to school.

The Taliban has ordered that only female teachers can take classes in girls’ high schools. Older male teachers are allowed only when there are not enough female teachers.

Durrani and others feared that trying to prevent teenage girls from education is just the first step towards something bigger and more dangerous.

The lack of women in the cabinet, Taliban officials passing judgment about women’s attire and perfume are seen as harbingers of something worse to come by many Afghan women.

“It’s a way of breaking a powerful chain. First, you keep girls from education so that they don’t  have the skills to work, and before you know it, you’ve deprived an entire generation from becoming part of society.”

have the skills to work, and before you know it, you’ve deprived an entire generation from becoming part of society.”

Earlier, the US and European envoys have been warned by Afghanistan’s new Taliban government that continued attempts to pressure them through sanctions will undermine security and could trigger a wave of economic refugees.

Acting foreign minister Amir Khan Muttaqi told Western diplomats at talks in Doha that “weakening the Afghan government is not in the interest of anyone because its negative effects will directly affect the world in (the) security sector and economic migration from the country”, according to a statement published late Tuesday.

The Taliban overthrew Afghanistan’s former US-backed government in August after a two-decade-long conflict, and have declared an Islamic emirate governed under the movement´s hardline interpretation of religious law but efforts to stabilize the country, still facing attacks from Daesh have been undermined by international sanctions: banks are running out of cash and civil servants are doing their jobs unpaid.

According to the statement from his spokesperson, Muttaqi told the Doha meeting: “We urge world countries to end existing sanctions and let banks operate normally so that charity  groups, organizations and the government can pay salaries to their staff with their own reserves and international financial assistance.”

groups, organizations and the government can pay salaries to their staff with their own reserves and international financial assistance.”

European countries in particular are concerned that if the Afghan economy collapses, a large number of migrants will set off for the continent, piling pressure on neighboring states such as Pakistan and Iran and eventually on EU borders.

Washington and the EU have said they are ready to back humanitarian initiatives in Afghanistan, but are wary of providing direct support to the Taliban without guarantees it will respect human rights, in particular women’s rights.

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has slammed the Taliban’s “broken” promises to Afghan women and girls, and urged the world to inject cash into Afghanistan in order to prevent its economic collapse.

“I am particularly alarmed to see promises made to Afghan women and girls by the Taliban being broken,” he told reporters on Monday in New York.

“I strongly appeal to the Taliban to keep their promises to women and girls and fulfil their obligations under international human rights and humanitarian law.”

Millions of teenage girls across Afghanistan still wait to return to school, while the Taliban allowed boys to attend classes last month. The move has raised concerns about the future of  female education under the Taliban, who have pledged to uphold the rights of girls and women in the country when they took over power in August.

female education under the Taliban, who have pledged to uphold the rights of girls and women in the country when they took over power in August.

The exclusion of girls at this time has aggravated fears that the Taliban could be returning to their hardline rule of the 1990s. During that time, women and girls were legally barred from education and employment.

The group has also named an all-male cabinet, and said that women could be included later.

Guterres said he is “alarmed” to see promises “be broken”, adding that gender equality is a priority for him.

“Broken promises lead to broken dreams for the women and girls of Afghanistan,” the UN chief said. “Women and girls need to be in the centre of attention,” he added.

In his address, Guterres also urged the international community to “inject liquidity into the Afghan economy to avoid collapse”.

“We need to find ways to help the economy breathe again … And this can be done without violating international laws,” he said.

James Bays, reporting from New York, said the timing of the UN chief’s remarks is “very important” as member states of the Group of 20 (G20) are expected to hold an extraordinary session “in the next 24 hours”.

The G20 is not going to “actually handover the (frozen) assets of Afghanistan … and give that to the Taliban government,” Bays said.

The G20 is not going to “actually handover the (frozen) assets of Afghanistan … and give that to the Taliban government,” Bays said.

The UN is working on a different plan to try and inject money into the Afghan economy by using “trust funds … one from the World Bank, one from the UN Development Program,” among others, Bays said.

“They’ll put the money into those trust funds and that money … will be used to pay for vital supplies, used for salaries of medical workers, used for teachers,” he added.

“That’s what the Secretary General is working on, and that’s what he’s trying to persuade the countries of the G20 to support.”

‘Positive relationships’

Guterres’s remarks came as a Taliban delegation was set to meet European Union representatives in Doha on Tuesday, according to acting foreign minister Amir Khan Muttaqi.

The meeting will follow the Taliban government’s first face-to-face talks with the United States.

“Tomorrow, we are meeting the EU representatives. We are having positive meetings with representatives of other countries,” Muttaqi said in the Qatari capital.

“We want positive relationships with the whole world. We believe in balanced international relations. We believe such a balanced relationship can save Afghanistan from instability,” he added.

Pressmediaofindia

Pressmediaofindia