07-07-2021

KABUL/ WASHINGTON/ ISLAMABAD: Western intelligence chiefs are worried. They have good reason to be.

The hurried departure this month of the remaining Western forces from Afghanistan, decreed by US President Joe Biden, has emboldened Taliban insurgents.

In recent days they have seized one district after another, overrunning bases where demoralised government troops have often surrendered or fled.

Now, say observers, the spectre of international terrorism is making an unwelcome return.

“The Biden withdrawal from Afghanistan makes a Taliban takeover inevitable and gives al-Qaeda the opportunity to rebuild its network, to the point where it could once again plot attacks around the world,” Dr Sajjan Gohel, a security and terrorism analyst, told the BBC.

That is certainly at the more pessimistic end of the spectrum but two things are certain here.

Firstly, the Taliban – the hardline Islamists who ruled Afghanistan from 1996-2001 with a rod of iron – are coming back in some form.

For now, they say they have no ambition to take Kabul, the capital, by force. But in large parts of the country they are already the dominant force and they have never dropped their demand to make the country an Islamic Emirate according to their own strict guidelines.

Secondly, al-Qaeda and its rival, the Islamic State in Khurasan Province (IS-KP), will be looking to profit from the departure of Western forces to expand their operations in Afghanistan.

Al-Qaeda and IS are already in Afghanistan. The country is simply too mountainous, the terrain too rugged, for there not to be numerous remote hiding places for these internationally proscribed terror groups to hide away in but up until now the Afghan government intelligence service, the NDS, working closely with US and other special forces, has been able to partly contain the threat.

Attacks and bombings have still taken place, but on countless occasions that we rarely hear about in public, tipoffs by human informants or an intercepted mobile phone call have resulted in swift and effective action by Afghan and Western special forces.

Operating from bases inside Afghanistan, they have often been able to react within minutes, landing by helicopter, sometime in the dead of night, catching their enemy by surprise.

That is now coming to an end.

‘The threat to Britain will grow’

‘The threat to Britain will grow’

The Taliban have made it clear this week that they expect any Western forces left behind – even those guarding Kabul airport or the US embassy – to be a violation of the Doha deal that commits all US forces to departing by 11 September.

They have vowed to attack any such remaining forces. Yet this week UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson is expected to chair a meeting of his government’s secretive National Security Council (NSC) to discuss just what military assistance Britain should be leaving in place.

The former chief of the Secret Intelligence Service, Sir Alex Younger, told Sky News that “the terror threat to Britain will grow if the West abandons Afghanistan”.

But here’s the dilemma: leave behind a few dozen SAS or other Special Forces operatives in the country, without the protective shield of US military bases and close air support, and they risk being hunted down by a resurgent Taliban.

Pull them out, as the Taliban have demanded, and the West has no means to react quickly to intelligence on terrorist activity.

So what exactly is the relationship between the Taliban and al-Qaeda?

Does a Taliban return to power in some form inevitably mean a return of al-Qaeda, with all its bases, its terror training camps and its hideous poison-gas experiments on dogs?

In short, the very things the US-led invasion of 2001 was intended to close down forever.

This question has been vexing Western intelligence chiefs for years. Twice now, in 2008 and again this year, classified British government assessments have been carelessly left lying around in public places, revealing to anyone who cared to read them how concerned the UK was about the link between the two groups.

Dr Gohel, who has been studying extremist groups in the region for years, was in no doubt.

“The Taliban is inseparable from al-Qaeda, with cultural, familial and political obligations from which it will remain unable to fully abandon, even were its leadership sincere in seeking to do so,” Dr Gohel of the Asia Pacific Foundation said.

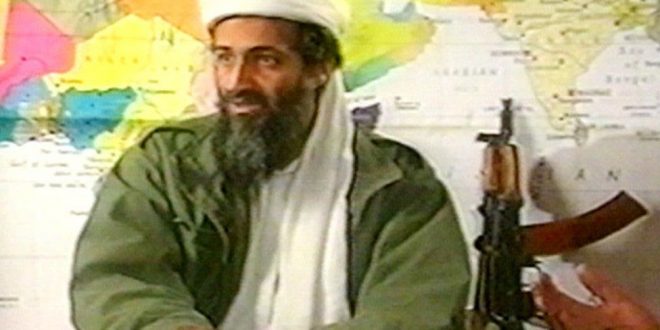

From the time that the al-Qaeda leader, Osama bin Laden, moved his operations from Sudan back to Afghanistan in 1996 up until 2001, the Taliban provided a safe haven for him.

Saudi Arabia, one of only three countries to recognise the Taliban government at the time, sent its intelligence chief, Prince Turki al-Faisal, to try to persuade the Taliban to hand over bin Laden.

They refused and it was from al-Qaeda’s Afghan base that the devastating 9/11 attacks were planned and directed.

But the UK’s Chief of Defence Staff, General Sir Nick Carter, who served several command tours in Afghanistan, believes the Taliban leadership may have learnt from their earlier mistakes.

He maintained that if the Taliban expect to share power, or seize it, then they will not want to be seen as international pariahs this time around.

And here lies the difficulty. Wiser heads among the Taliban, especially those who have tasted the good life in the air-conditioned shopping malls of Doha during the recent peace negotiations, may well argue for a clean break with al-Qaeda in order to secure international acceptance but in a vast, thinly governed country like Afghanistan, it is by no means certain that even a future Taliban government could contain al-Qaeda, which could easily embed its cells unseen within villages and remote valleys.

Ultimately what both al-Qaeda and the Islamic State group need to thrive is a chaotic, unstable situation. All the signs indicate that in Afghanistan, they are about to get it. (BBC)

Pressmediaofindia

Pressmediaofindia