17-09-2024

TASMANIA: For months, an unusual monument sat in an oak-lined square at the heart of Tasmania’s capital: a pair of severed bronze feet.

A statue of renowned surgeon-turned-premier William Crowther had loomed over the park in Hobart for more than a century but one evening in May, it was chopped down at the ankles and the words “what goes around” graffitied on its sandstone base.

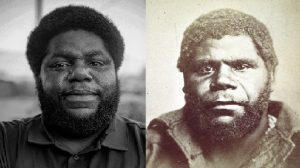

It was a throwback to another night more than 150 years ago, when Crowther allegedly broke into a morgue, sliced open an Aboriginal leader’s head and stole his skull – triggering a grim tussle over the remaining body parts.

It was a throwback to another night more than 150 years ago, when Crowther allegedly broke into a morgue, sliced open an Aboriginal leader’s head and stole his skull – triggering a grim tussle over the remaining body parts.

Tasmania had become the centre of colonizer efforts to eradicate Aboriginal people in Australia. And the sailor on the slab, William Lanne was touted as the last man on the island, making his remains a twisted trophy for white physicians.

Some see Crowther as an unfairly maligned man of his time, and his effigy as an important part of the state’s history, warts and all but for Lanne’s descendants, it represents colonial brutality, the dehumanizing myth that Tasmanian Aboriginal people are extinct, and the whitewashing of the island’s past.

“You walk around the city anywhere and you’d never know Aborigines were here,” Aboriginal activist Nala Mansell says.

Now the dismembered statue has become a symbol of a city and a nation struggling to reckon with its darkest chapters.

The extinction lie

Few places encapsulate the issue quite like Risdon Cove called piyura kitina by the Palawa Aboriginal people.

Tucked beside a creek, a monument proudly marks it as the first British settlement on what was then called Van Diemen’s Land.

For Tasmanian Aboriginal people, though, this hillside on the outskirts of Hobart is “ground zero for invasion”.

“It’s the first landing and not coincidentally the first massacre (of our people),” Nunami Sculthorpe-Green tells media one overcast afternoon.

Startled from their reverie, flurries of native hens which piyura kitina is named after scatter over the mossy grass as we arrive.

Startled from their reverie, flurries of native hens which piyura kitina is named after scatter over the mossy grass as we arrive.

A wallaby hastily bounds towards sparse gum trees. It’s from that direction that Mumirimina men, women and children would have come down the slope on 3 May 1804, singing as they hunted kangaroos.

They were met with muskets and cannons.

The events of that day and the death toll are disputed. What is not contested is that this marked the start of a determined effort by British settlers to get rid of the original Tasmanians, nine nations of up to 15,000 people.

War broke out and Aboriginal people were hunted across the island, the survivors rounded up and sent to what have been described as death camps.

“If that happened anywhere in the world today, it would be referred to as ethnic cleansing,” says Greg Lehman, a Palawa professor of history.

Ripped from his homelands as a child, Lanne survived two of those camps before living out his final years as a shipmate and beloved advocate for his people.

Even before he died of disease in 1869, aged only 34, letters show that powerful men in Hobart had begun scheming.

“There’s no way that that young man was going to be allowed to lie in a grave. No way,” historian Cassandra Pybus tells media.

The theft of Aboriginal remains had long been normalized, she says, but reached a fever pitch in Tasmania as the number of its original inhabitants dwindled. (Int’l News Desk)

Pressmediaofindia

Pressmediaofindia